| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| |

|

||||||||||||||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

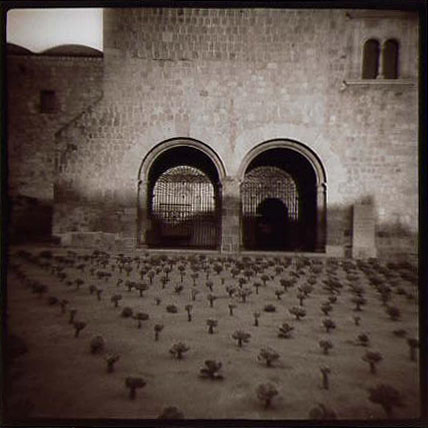

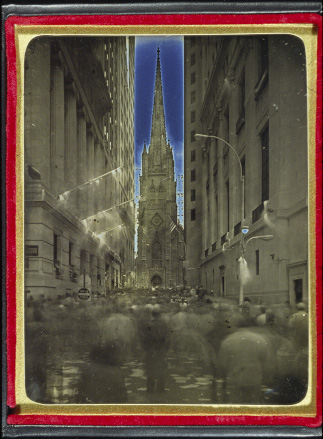

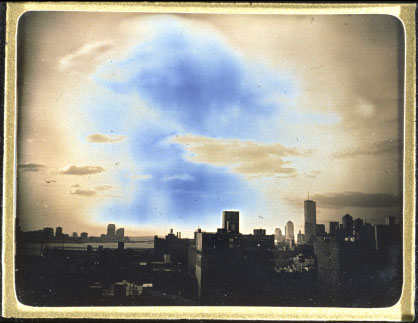

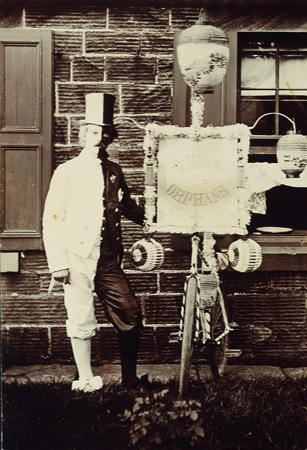

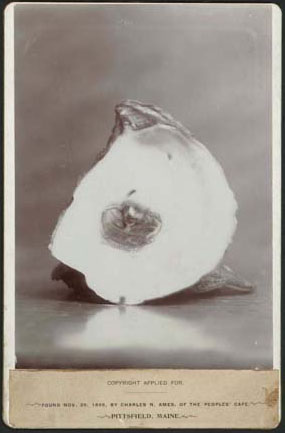

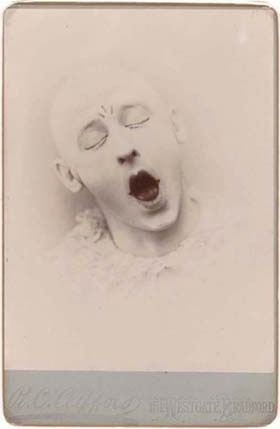

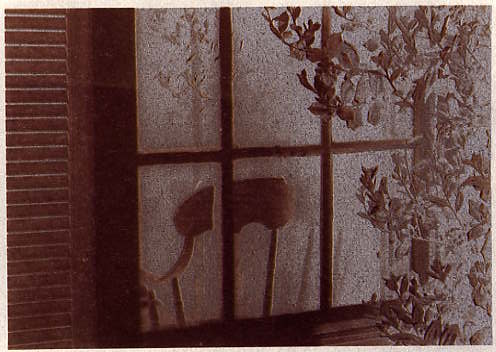

I confess I’ve rarely been completely satisfied with “straight” black and white (gelatin silver) photography. Over the past 25 years I’ve employed numerous devices to extend the dialogue with my images: I have gathered them into handmade books, collaged them, grouped them together onto mats, and even made paintings with them or based upon them. What I have endeavored to do is to make each step in the photographic process another beginning point – to use each result as a further point of departure. My most recent fascination – ongoing since the early ‘90’s – is with toning, most particularly split-toning. To speak of split-toning in an authoritative way is, if not dangerous, at least problematic. Emmet Gowin – who was so helpful when I was first struggling with these processes – recently said to me that no one, chemist or otherwise, has ever explained to his satisfaction exactly what these split-processes entail. (see his interview and spit-toned images in Camera Arts, December/January ’98-’99). Gowin’s understanding of split toning has come mainly through direct experience. Indeed, much of what I will discuss here springs from my own direct and very subjective observation. I’d like to suggest a simple definition: split-tones refer to both warm and cold tones simultaneously present in an image. Whereas conventional toning (sepia, for example) will render a print a uniform chocolate brown color, split-toning typically yields shades of reds and blues - occasionally even greens and violets - and therein lies the difference. The effects may range from subtle to extravagant. Generally speaking, split-tones are the result of chemical toners used after normal processing and fixing (more about this in the next issue). Split-toning is a generic, somewhat mercurial term which is used to describe the deliberate attempt at tonal splits in the darkroom. However, split effects have been with photography from the very beginning and may well have formed an historical precedent for many modern practitioners of these processes. The issue is therefore, perhaps, one of intent. The question might better be: when were these visual effects first specifically sought out and deliberately attempted? Certainly, among the first of the published efforts was Olivia Parker’s beautiful book, Signs of Life, in 1978 (now out of print and, sadly, difficult to find). I was interested to learn in my conversation with Gowin that he first started experimenting with toners in the late 60’s while he was learning 19th century processes in school. I first began experimenting with split-toning in 1993-94 while stalling for time to experiment with 19th century processes such as albumen or platinum. I have a long and abiding interest in photographs from the 19th century and I was hoping to bring to my own work some of the soulfulness and richness I associate with so many antique images. What I’d come to appreciate with the antique images was how intimately intertwined image and process can become – that sense of inevitability when an image is coupled successfully with the “right” process. I was in search of something for my images which they seemed to be asking for - something I thought I understood - but I was delivered to something that took some time to fully appreciate. However, I had no idea how profoundly satisfying working with these old and esoteric processes would become. Photographic images have historically demonstrated a range of subtle to exotic coloration. Daguerreotypes, for example, readily “split” in an area of intense exposure. While the effect is not, strictly speaking, chemically induced (it’s actually solarization), dags often exhibit a strikingly beautiful deep blue tonal split that almost seems to jump from the surface of the plate. This almost three-dimensionality I also associate with split-toning.

Albumen prints when toned (generally in gold-based toners) yield a wide range of possible color variations, including, on occasion, tonal splits. Whether or not this was ever done historically in a deliberate way is open to debate.

As photographic papers became commercially available a great many of them would tone with exotic results: among the more exotic were the bromide papers of the 1880’s and ‘90’s. These were the first of the gelatin-based factory-produced papers and they remained in scattered use through the 1930’ s. These images often possess a striking blue-red split that makes them easily identifiable. And too, commercially available printing out papers (POP), both vintage and modern, will often split when toned (witness Atget’s vintage work and Linda Connor’s contemporary work).

Then there are the tonal splits that occur “naturally” as a result of inadequate fixing and/or washing and subsequent exposure to the atmosphere. Many older silver prints display an apparent splitting of their tones for exactly this reason - in effect, Gowin explains, a selective hypo-alum sepia toning of the print. He noted as many as one third of the prints in the recent Carleton Watkins exhibit at New York’s Metropolitan Museum showed signs of this effect.

Split effects can also be created from dual processing of hand coated papers: for instance, a layer of platinum under (or over) a layer of gum bichromate – a common practice at the turn of the last century, and a practice of which Steichen was a master. It’s interesting to note that some modern practitioners of 19th century processes have resurrected this habit today.

Photographs, in all their various forms, have nearly always been chemically toned as a way to heighten permanence – color changes were largely a collateral effect. Daguerreotypes hadn’t been around more than three or fours years before people realized that gold chloride and hypo, upon heating with a flame, would gild the silver on the plate and render a significantly more durable image. This archival benefit has been the major historical role for toners. It’s just that more recently (say the past 50 years), toning practices have been largely confined to archival enhancement - with any possible visual effects being systematically avoided. My fascination with toners is specifically about the visual effects that are possible. It would seem a somewhat eccentric appreciation of the history of photography, or perhaps more accurately, the history of the photograph, might be required to fully appreciate the attractions of split-toning. I think it’s safe to suggest that all the photographers today who use some form of split-toning in their work (including Gowin, Thomas Joshua Cooper, Linda Conner, Lynn Davis, Linda Butler, Christopher James and Craig Stevens) seem intimately connected to photography’s past in some uniquely personal way. Each of these photographers seems to intuitively comprehend how the photographic process ultimately impacts the image’s emotional impact. I believe this aesthetic understanding flows directly out of a 19th century sensibility. However, despite the serious work being done with these split-processes there remains resistance and misunderstanding about the effects. Some of this resistance lies in photography’s history: For most of the 20th century (especially the second half), photography in the United States has felt an obligation to be straight, truthful, and unaffected. Strand, Weston and Adams (to name only the most influential) vilified pictorialism, abhorring any mark of hand or “artful” device – and we still labor heavily under their prejudices today. Photography today is still very much linked to its content. Judy Seigel, in her superb World Journal of Post-Factory Photography, puts it thus: “…painting was declared its own event, while photography was declared a faithful copy of another, real event.” Of course the issue of verisimilitude has haunted photography since its first days - people just want to believe a photograph. But as Frederick Sommer pointed out, there is an enormous difference between “a thing seen” and a photograph of “a thing seen.” He acknowledged the photograph is reality – but noted it is a photographic one. He further suggested a photograph is a thing seen in its own right. Small wonder split-toning remains on the fringes of understanding and acceptance in mainstream photographic circles. Perhaps part of the attraction lies in at least a partial disengagement from the content of the photograph: an appreciation of the transformation that’s possible when we take a photograph out of the realm of document and into the realm of image. I have again and again found this transformation most easily apprehended with antique images: with these images we are frequently left knowing nothing of the photographers nor of the circumstances in which they worked – which leaves us to contemplate the unencumbered evidence of the photograph itself…. In the next issue I will offer specific, hands-on, working formulas and notes. The only prerequisite for their use will be a willingness to suspend the desire to “mastermind” a preconceived result, and the openness required to entrust oneself entirely to the materials and to the processes themselves: to become a midwife to the images.

|

|||||||||||||||